THE BABY: Home Is Where The Horror Is

A common misconception with up-and-coming filmmakers is that a film must test the boundaries of explicitness to shock. The truth is that extreme content is just one tool in the filmmakers arsenal, the simplest to use and the least effective if leaned on too heavily. Real horror comes from delving into the psychology, morality and emotions of the audience. If you can do that with skill, you don't have to pile on the explicit shocks because you'll be getting the audience where it counts - in the most vulnerable corners of their minds. The Baby is exactly this kind of horror film because it creeps the viewer out on a visceral yet purely psychological level. It all begins with the premise: Ann Gentry (Anjanette Comer) is a social worker who has chosen to take on the case of the Wadsworth family. Mrs. Wadsworth (Ruth Roman) is the matriarch of the clan and she lives in a Los Angeles home with her grown daughters, Germaine (Marianna Hill) and Alba (Suzanne Zenor).However, the focus of Ann's work is the only man in the Wadsworth home: Baby (David Manzy), a grown man so mentally handicapped that he has the mentality and abilities of an infant. He doesn't speak, he crawls instead of walks and is totally dependent on the care of his mother and sisters. Ann quickly becomes suspicious of Baby's family, as it seems they want Baby to remain their helpless little boy forever. She engages in a battle of wills with Mrs. Wadsworth, trying to get Baby freed from his prison of a home. As the stakes get raised, it is revealed that Ann has a trauma of her own to cope with - and that the Wadsworth clan is willing to go to drastic measures to keep Baby at home.

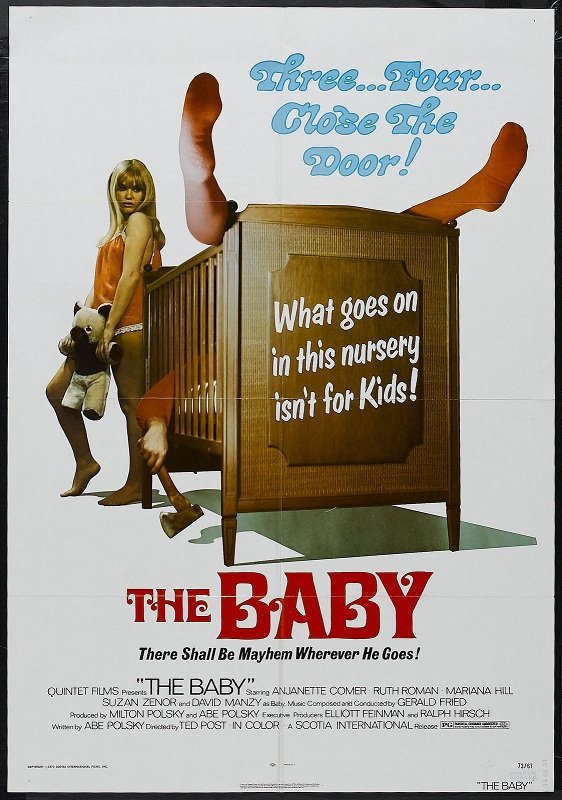

The Baby is exactly this kind of horror film because it creeps the viewer out on a visceral yet purely psychological level. It all begins with the premise: Ann Gentry (Anjanette Comer) is a social worker who has chosen to take on the case of the Wadsworth family. Mrs. Wadsworth (Ruth Roman) is the matriarch of the clan and she lives in a Los Angeles home with her grown daughters, Germaine (Marianna Hill) and Alba (Suzanne Zenor).However, the focus of Ann's work is the only man in the Wadsworth home: Baby (David Manzy), a grown man so mentally handicapped that he has the mentality and abilities of an infant. He doesn't speak, he crawls instead of walks and is totally dependent on the care of his mother and sisters. Ann quickly becomes suspicious of Baby's family, as it seems they want Baby to remain their helpless little boy forever. She engages in a battle of wills with Mrs. Wadsworth, trying to get Baby freed from his prison of a home. As the stakes get raised, it is revealed that Ann has a trauma of her own to cope with - and that the Wadsworth clan is willing to go to drastic measures to keep Baby at home. With a premise that outlandish, you could be excused for expecting The Baby to be a crazy camp-fest packed with lurid shocks. However, the film is disarmingly subtle in its attack on the viewer's psyche. Screenwriter Abe Polsky has enough confidence in his premise to build its intensity in a gradual fashion, gradually ratcheting up the tension as the different, disturbing angles of the storyline slowly come into view. By the time the film reaches its finale, the steady slow-burn approach of the script ensures that it has a genuine emotional and psychological punch.Better yet, Polsky doesn't lean on the bizarre nature of his concept to make the film work. He develops the story and its themes with unexpected depth: the film has a lot to say about child abuse, the social and psychological dynamic between a mother and her children and

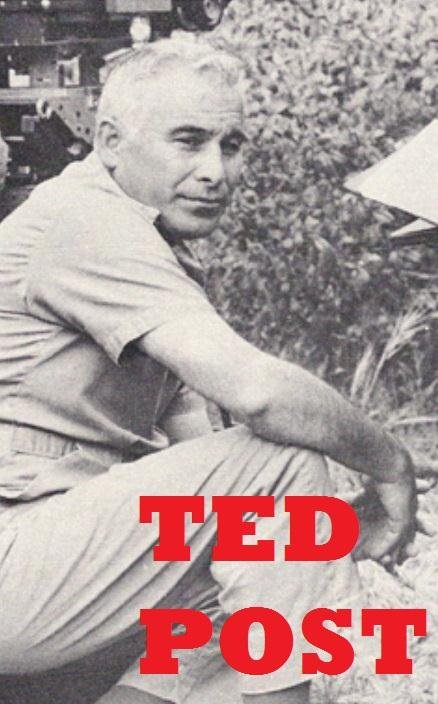

With a premise that outlandish, you could be excused for expecting The Baby to be a crazy camp-fest packed with lurid shocks. However, the film is disarmingly subtle in its attack on the viewer's psyche. Screenwriter Abe Polsky has enough confidence in his premise to build its intensity in a gradual fashion, gradually ratcheting up the tension as the different, disturbing angles of the storyline slowly come into view. By the time the film reaches its finale, the steady slow-burn approach of the script ensures that it has a genuine emotional and psychological punch.Better yet, Polsky doesn't lean on the bizarre nature of his concept to make the film work. He develops the story and its themes with unexpected depth: the film has a lot to say about child abuse, the social and psychological dynamic between a mother and her children and  the enduring trauma that can be caused by a hole in the family unit. The author also invests his story with three-dimensional characters that give the viewer a genuine reason to get invested in his outré plotline - and it's worth noting that this is a rare horror film where women play almost all the crucial roles.The subtlety and craftsmanship of the scripting extends to Ted Post's direction. Post was a veteran journeyman director with tons of credits in both t.v. and film - including two for Clint Eastwood, Hang 'Em High and Magnum Force - so he brings a surefooted, unfussy sense of craft to the proceedings. He's savvy enough to understand that the film's bizarre

the enduring trauma that can be caused by a hole in the family unit. The author also invests his story with three-dimensional characters that give the viewer a genuine reason to get invested in his outré plotline - and it's worth noting that this is a rare horror film where women play almost all the crucial roles.The subtlety and craftsmanship of the scripting extends to Ted Post's direction. Post was a veteran journeyman director with tons of credits in both t.v. and film - including two for Clint Eastwood, Hang 'Em High and Magnum Force - so he brings a surefooted, unfussy sense of craft to the proceedings. He's savvy enough to understand that the film's bizarre  premise speaks for itself so he avoids flashy frills and sledgehammer techniques. That said, when it's time to go for the throat - particularly during the tense finale - he brings a confident verve to the film's mechanics of suspense.Post is also to be commended for getting intense but controlled performances from his cast. This is a key reason for why The Baby is as effective as it is: the actors understand that the threat of someone coming unglued carries more power than an actual expression of hysteria itself.

premise speaks for itself so he avoids flashy frills and sledgehammer techniques. That said, when it's time to go for the throat - particularly during the tense finale - he brings a confident verve to the film's mechanics of suspense.Post is also to be commended for getting intense but controlled performances from his cast. This is a key reason for why The Baby is as effective as it is: the actors understand that the threat of someone coming unglued carries more power than an actual expression of hysteria itself. Comer makes for a sympathetic audience-identification figure heroine, yet also artfully reveals a troubled side to her character that gives her scenes an added charge. Hill and Zenor provide nice a contrast to each other as the daughters: Hill has a haunted quality that is creepy in a quiet way while Zenor brings a casual sadism to her role guaranteed to unnerve the viewer. However, it is Roman who steals the show as the matriarch, finding a more modulated version of the battle-axe characters that Joan Crawford and Bette Davis made famous in their 1960's "crazy old lady" horror flicks.

Comer makes for a sympathetic audience-identification figure heroine, yet also artfully reveals a troubled side to her character that gives her scenes an added charge. Hill and Zenor provide nice a contrast to each other as the daughters: Hill has a haunted quality that is creepy in a quiet way while Zenor brings a casual sadism to her role guaranteed to unnerve the viewer. However, it is Roman who steals the show as the matriarch, finding a more modulated version of the battle-axe characters that Joan Crawford and Bette Davis made famous in their 1960's "crazy old lady" horror flicks. It's also worth noting that Manzy delivers a truly impressive performance as the title character. More than any other element of the film, his character had the greatest potential of slipping into a campiness or self-conscious strangeness that could have sunk the entire film. Thus, it is a pleasure to acknowledge that Manzy plays the role with great care, living up to the eccentric concept behind the character but informing Baby with a level of humanity and innocence that makes the audience sympathetic to his plight (once they get over the shock of who he is). His facial expressions and body language sell the character's odd nature without overstating it - and Manzy's work is thus the engine that drives the film.Finally, this review would be remiss if it didn't briefly mention the film's stunner of an ending. Without getting into spoilers, The Baby has the kind of coda that hits you like a ton of bricks even if you see it coming. Its final moments manage to be tragic, oddly moving, darkly funny and emotionally cathartic all at once. Simply put, it's one Your Humble Reviewer's favorite endings in the history of cinema.In closing, it might be a cliché to say "they don't make 'em like they used to" - but The Baby is the kind of film for which this cliché was invented. Even way back when, they didn't make 'em like this - and this film retains every ounce of its quietly subversive power. For that reason and many more, The Baby gets Schlockmania's highest recommendation.

It's also worth noting that Manzy delivers a truly impressive performance as the title character. More than any other element of the film, his character had the greatest potential of slipping into a campiness or self-conscious strangeness that could have sunk the entire film. Thus, it is a pleasure to acknowledge that Manzy plays the role with great care, living up to the eccentric concept behind the character but informing Baby with a level of humanity and innocence that makes the audience sympathetic to his plight (once they get over the shock of who he is). His facial expressions and body language sell the character's odd nature without overstating it - and Manzy's work is thus the engine that drives the film.Finally, this review would be remiss if it didn't briefly mention the film's stunner of an ending. Without getting into spoilers, The Baby has the kind of coda that hits you like a ton of bricks even if you see it coming. Its final moments manage to be tragic, oddly moving, darkly funny and emotionally cathartic all at once. Simply put, it's one Your Humble Reviewer's favorite endings in the history of cinema.In closing, it might be a cliché to say "they don't make 'em like they used to" - but The Baby is the kind of film for which this cliché was invented. Even way back when, they didn't make 'em like this - and this film retains every ounce of its quietly subversive power. For that reason and many more, The Baby gets Schlockmania's highest recommendation.