DELIVERANCE: When Art Spawns A Schlock Subgenre

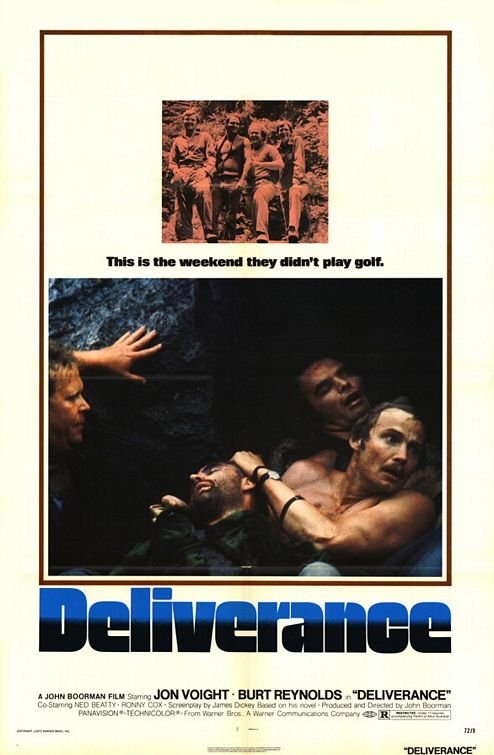

First things first: Deliverance is a not a schlock film. For many reasons that will be explored momentarily, it's one of best American films of the 1970's and a challenging work of art that remains potent today. However, it is also crucially important to the world of schlock because it spawned one of the greatest 1970's subgenres of exploitation filmmaking.Deliverance is based on a novel by James Dickey, a Southern poet who made his first venture into narrative storytelling with this book and also adapted said tome for the silver screen. The plotline seems simple enough on its surface: a quartet of  city-dwelling men - Lewis (Burt Reynolds), Ed (Jon Voight), Bobby (Ned Beatty) and Drew (Ronny Cox) - travel to the country to take a canoe journey down a Georgia river that is about to be dammed up. Lewis is the macho man of the group and its nominal leader, with Ed functioning as his meek alter ego and Bobby and Drew basically along for the ride.Though the quartet is clearly out of place in their rural surroundings and the locals seem skeptical of their ambition, Lewis's bravado is enough to sustain the group and they set off down the river. Things go well enough until Ed and Bobby get ahead of the other canoe and stop at the wrong section of riverbank. They run into a pair of gun-toting mountain men (Bill McKinney and Herbert Coward) who tie up Ed while one rapes Bobby. Lewis shows up in time to kill one of the attackers, thus setting into motion a chain of events that will leave two more people dead and everyone in the group changed forever.It's a grim, unn

city-dwelling men - Lewis (Burt Reynolds), Ed (Jon Voight), Bobby (Ned Beatty) and Drew (Ronny Cox) - travel to the country to take a canoe journey down a Georgia river that is about to be dammed up. Lewis is the macho man of the group and its nominal leader, with Ed functioning as his meek alter ego and Bobby and Drew basically along for the ride.Though the quartet is clearly out of place in their rural surroundings and the locals seem skeptical of their ambition, Lewis's bravado is enough to sustain the group and they set off down the river. Things go well enough until Ed and Bobby get ahead of the other canoe and stop at the wrong section of riverbank. They run into a pair of gun-toting mountain men (Bill McKinney and Herbert Coward) who tie up Ed while one rapes Bobby. Lewis shows up in time to kill one of the attackers, thus setting into motion a chain of events that will leave two more people dead and everyone in the group changed forever.It's a grim, unn erving scenario for a thriller and Deliverance delivers everything it promises: the infamous "squeal like a pig" sequence is a white-knuckle squirmfest of the first order, the plot reversals that follow are surprising (and merciless) and the film remains tense and suspenseful to the very end. John Boorman directs the story with a careful eye and judiciously calibrated pacing while Vilmos Zsigmond's evocative, atmospheric lensing helps transform the forest and the river from settings into characters that dominate the storyline as much as any of the men.Better yet, the performances are consistently excellent. Reynolds informs what could have been a conventional macho-man role with an unexpected soulfulness and Voight sells on the gravity of every situation with a convincing method-style performance as a mild-mannered soul who is forced to find his inner warrior. Beatty enacts a difficult role in a dignified, emotionally believable style and Cox scores big with a scene where he argues with Reynolds argue about the morality of their actions. Better yet, McKinney and Coward will scare the hell out of you as the casually vicious attackers. It's also worth noting that Dickey has a small role near the end as a sheriff and acquits himself nicely in a memorable scene where he goes toe to toe with Voight and Beatty.

erving scenario for a thriller and Deliverance delivers everything it promises: the infamous "squeal like a pig" sequence is a white-knuckle squirmfest of the first order, the plot reversals that follow are surprising (and merciless) and the film remains tense and suspenseful to the very end. John Boorman directs the story with a careful eye and judiciously calibrated pacing while Vilmos Zsigmond's evocative, atmospheric lensing helps transform the forest and the river from settings into characters that dominate the storyline as much as any of the men.Better yet, the performances are consistently excellent. Reynolds informs what could have been a conventional macho-man role with an unexpected soulfulness and Voight sells on the gravity of every situation with a convincing method-style performance as a mild-mannered soul who is forced to find his inner warrior. Beatty enacts a difficult role in a dignified, emotionally believable style and Cox scores big with a scene where he argues with Reynolds argue about the morality of their actions. Better yet, McKinney and Coward will scare the hell out of you as the casually vicious attackers. It's also worth noting that Dickey has a small role near the end as a sheriff and acquits himself nicely in a memorable scene where he goes toe to toe with Voight and Beatty. However, Deliverance is much more than a well-made thriller. Its ability to haunt a viewer comes from a carefully woven series of themes that inform the film's story from start to finish. The film uses the river journey as a metaphor that allows it to explore the tenuous relationship between man and nature: the river and a mountainside prove to be challenging and sometimes downright adversarial to the men, perhaps as a retaliation for the cavalier treatment they receive from their unappreciative human inhabitants.Also, the film explores the narrow line separating civilization from savagery (a discussion of law and the created morality it reflects is a powerful moment) and it uses Ed's character arc to explore what it means to be a man as well as the rites of passage one must undergo to achieve that status. It's not the first film to explore such themes but it handles them in a thoughtful, non-didactic style that leaves the audience room to figure out its own take on these subjects - and the fact that it juggles such diverse thematic aims with skill and precision ensures its enduring status as a classic.

However, Deliverance is much more than a well-made thriller. Its ability to haunt a viewer comes from a carefully woven series of themes that inform the film's story from start to finish. The film uses the river journey as a metaphor that allows it to explore the tenuous relationship between man and nature: the river and a mountainside prove to be challenging and sometimes downright adversarial to the men, perhaps as a retaliation for the cavalier treatment they receive from their unappreciative human inhabitants.Also, the film explores the narrow line separating civilization from savagery (a discussion of law and the created morality it reflects is a powerful moment) and it uses Ed's character arc to explore what it means to be a man as well as the rites of passage one must undergo to achieve that status. It's not the first film to explore such themes but it handles them in a thoughtful, non-didactic style that leaves the audience room to figure out its own take on these subjects - and the fact that it juggles such diverse thematic aims with skill and precision ensures its enduring status as a classic. Finally, Deliverance is hugely important to the world of schlock because its success set into motion what would become known as the "Southern Discomfort" subgenre. This phrase refers a type of exploitation film that plays on the city slicker's fear of rural territories by presenting stories in which unassuming city folk venture into the country and run afoul of the wrong local yokels, thus leading to tragedy (as well as highly exploitable action, suspense and sleaze). Most of these films would focus on mayhem instead of the powerful themes that Dickey explores but they're all cinematic children of Deliverance nonetheless.In short, Deliverance was, is and will always be a landmark cinematic moment. Whether you're coming from the artsy side of the aisle or the schlocky side, it packs a punch powerful enough to take on all comers.

Finally, Deliverance is hugely important to the world of schlock because its success set into motion what would become known as the "Southern Discomfort" subgenre. This phrase refers a type of exploitation film that plays on the city slicker's fear of rural territories by presenting stories in which unassuming city folk venture into the country and run afoul of the wrong local yokels, thus leading to tragedy (as well as highly exploitable action, suspense and sleaze). Most of these films would focus on mayhem instead of the powerful themes that Dickey explores but they're all cinematic children of Deliverance nonetheless.In short, Deliverance was, is and will always be a landmark cinematic moment. Whether you're coming from the artsy side of the aisle or the schlocky side, it packs a punch powerful enough to take on all comers.