DRIVE: The Alchemy That Transforms Pulp Into Art

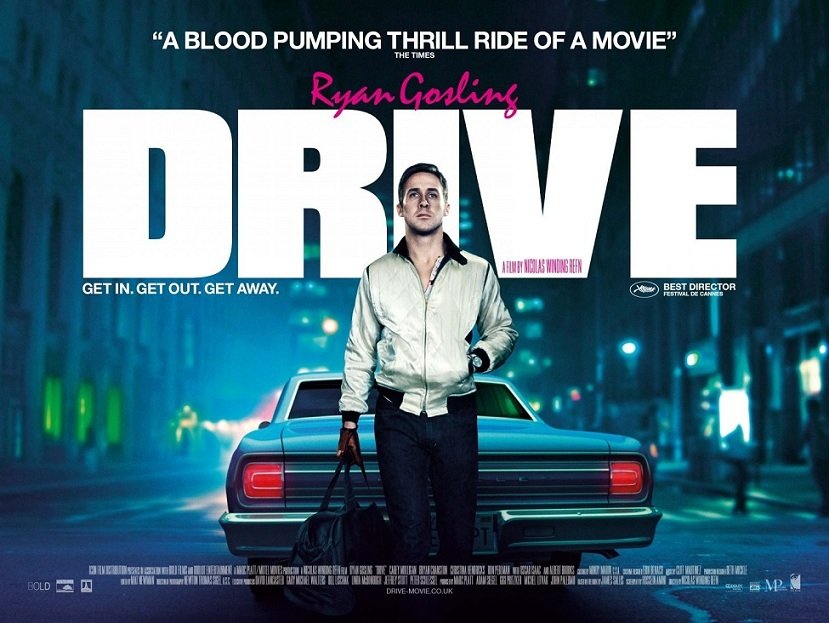

This review throws out the Schlockmania rulebook because Drive is not schlock. However, it deserves mention on this blog for two reasons. The first is that it takes pulp fiction archetypes and conventions and reconfigures them in an interesting way, creating something beautiful enough in its craft to qualify as an arthouse film while skillfully evading the pretension that often comes with such a label. It's also the best directed film Your Humble Reviewer has seen this year. Drive begins with a noir-ish plotline, adapted from a novel by James Sallis, that has echoes of Thief and The Driver. Driver (Ryan Gosling) leads a simple, solitary life, dividing his time between working as a stunt driver in movies and doing getaway-car work provided by his mentor/day-job employer, Shannon (Bryan Cranston). He is a cipher-like presence but emotions lurk behind his mute, blank exterior. Those emotions find a focus when Driver becomes involved with Irene (Carey Mulligan), a young mother whose husband is in prison.

Drive begins with a noir-ish plotline, adapted from a novel by James Sallis, that has echoes of Thief and The Driver. Driver (Ryan Gosling) leads a simple, solitary life, dividing his time between working as a stunt driver in movies and doing getaway-car work provided by his mentor/day-job employer, Shannon (Bryan Cranston). He is a cipher-like presence but emotions lurk behind his mute, blank exterior. Those emotions find a focus when Driver becomes involved with Irene (Carey Mulligan), a young mother whose husband is in prison. However, Driver and Irene's brief idyll ends when her husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) returns home and she takes him back. Unfortunately for everyone, he's in debt to some crooks for protection money and they are threatening his family if he doesn't pull a job for them. Driver signs on to handle the getaway car... and the rest is best left to viewers to discover for themselves, for this is where Drive takes its familiar genre elements into unpredictable territory that is dazzling and shocking by turns.

However, Driver and Irene's brief idyll ends when her husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) returns home and she takes him back. Unfortunately for everyone, he's in debt to some crooks for protection money and they are threatening his family if he doesn't pull a job for them. Driver signs on to handle the getaway car... and the rest is best left to viewers to discover for themselves, for this is where Drive takes its familiar genre elements into unpredictable territory that is dazzling and shocking by turns. The end result is both subversive and exhilarating. Some less attentive critics have complained that Drive recycles stock elements, which suggests they weren't paying attention. Drive does fascinating things with its archetypes, especially with the hero: without getting too deeply into spoilers, the viewer is led to expect redemption for him in the early scenes but what follows reveals a darker nature to the character than is first shown. Other characters offer similar twists of expectations, especially Bernie Rose (Albert Brooks), a crime kingpin who is played for humor at first but ultimately reveals the brutal instincts that help him achieve his "boss" status.

The end result is both subversive and exhilarating. Some less attentive critics have complained that Drive recycles stock elements, which suggests they weren't paying attention. Drive does fascinating things with its archetypes, especially with the hero: without getting too deeply into spoilers, the viewer is led to expect redemption for him in the early scenes but what follows reveals a darker nature to the character than is first shown. Other characters offer similar twists of expectations, especially Bernie Rose (Albert Brooks), a crime kingpin who is played for humor at first but ultimately reveals the brutal instincts that help him achieve his "boss" status. Along similar lines, as the second half of the film plows into dark territory, viewers come to realize that the film is stripping away the romanticized elements of the crime story to reveal the disturbing nature of its essential elements. At the same time, Drive finds untapped elements of humanity in the human wreckage that litters its landscape: everyone here has a dream and each is held back from achieving it due to destructive relationships that lead them further down a troubled path. Hossein Amini's lean script does wonders by delivering this sort of thematic complexity through a clean, sparsely-detailed narrative laced with terse yet well-crafted dialogue. It never overplays its hand and as a result, its surprises pack a wallop.

Along similar lines, as the second half of the film plows into dark territory, viewers come to realize that the film is stripping away the romanticized elements of the crime story to reveal the disturbing nature of its essential elements. At the same time, Drive finds untapped elements of humanity in the human wreckage that litters its landscape: everyone here has a dream and each is held back from achieving it due to destructive relationships that lead them further down a troubled path. Hossein Amini's lean script does wonders by delivering this sort of thematic complexity through a clean, sparsely-detailed narrative laced with terse yet well-crafted dialogue. It never overplays its hand and as a result, its surprises pack a wallop. That said, smart scripting is merely the bedrock of all the inventive things going on here. The performances reflect the surprising depth of the material: Gosling manages to hold the viewer's attention with a minimalist yet intense performance in which each shift of facial expression speaks volumes. Mulligan builds a convincing chemistry with him, allowing the film to have a sense of romance that keeps the viewer engaged even with things get shocking, and Cranston brings gravitas to the role of the crooked but charming mentor. Brooks is revelatory as the sly kingpin, throwing aside the neurotic persona he has developed over the years to create a surprising and convincing portrait of an L.A.-styled crook. He also gets able support from Ron Perlman in a deliberately cartoonish (but well-judged) turn as Brooks' sleazy partner in crime.Howeve

That said, smart scripting is merely the bedrock of all the inventive things going on here. The performances reflect the surprising depth of the material: Gosling manages to hold the viewer's attention with a minimalist yet intense performance in which each shift of facial expression speaks volumes. Mulligan builds a convincing chemistry with him, allowing the film to have a sense of romance that keeps the viewer engaged even with things get shocking, and Cranston brings gravitas to the role of the crooked but charming mentor. Brooks is revelatory as the sly kingpin, throwing aside the neurotic persona he has developed over the years to create a surprising and convincing portrait of an L.A.-styled crook. He also gets able support from Ron Perlman in a deliberately cartoonish (but well-judged) turn as Brooks' sleazy partner in crime.Howeve r, the crucial thing that transforms pulp into art in Drive is the direction of Nicholas Winding Refn. His technique is unfailingly precise: the framing of every shot is stylishly specific, every camera move is judiciously deployed and every sequence is edited in a seamless manner. The end is incredibly stylish yet has an economy to its layout that allows the viewer to savor the visual storytelling skill on display.It helps that Winding-Refn has brought in some gifted technicians to achieve the film's sumptuous look and sound: Newton Thomas Sigel's photography allows L.A. to show the

r, the crucial thing that transforms pulp into art in Drive is the direction of Nicholas Winding Refn. His technique is unfailingly precise: the framing of every shot is stylishly specific, every camera move is judiciously deployed and every sequence is edited in a seamless manner. The end is incredibly stylish yet has an economy to its layout that allows the viewer to savor the visual storytelling skill on display.It helps that Winding-Refn has brought in some gifted technicians to achieve the film's sumptuous look and sound: Newton Thomas Sigel's photography allows L.A. to show the  kind of ghostly beauty it hasn't displayed in a film since Collateral and the amazing score from Cliff Martinez has a steely yet glossy feel that evokes early 1980's Tangerine Dream (there are also some brilliantly inspired song choices, mostly from modern new-wave revivalists).That said, don't get the impression that style is used as a buffer to make things easy on the viewer. Winding-Refn's seductive grasp of technique is used to disarm the viewer so when the second half's surprises kick in - along with a few genuinely shocking sequences of

kind of ghostly beauty it hasn't displayed in a film since Collateral and the amazing score from Cliff Martinez has a steely yet glossy feel that evokes early 1980's Tangerine Dream (there are also some brilliantly inspired song choices, mostly from modern new-wave revivalists).That said, don't get the impression that style is used as a buffer to make things easy on the viewer. Winding-Refn's seductive grasp of technique is used to disarm the viewer so when the second half's surprises kick in - along with a few genuinely shocking sequences of  violence - the audience is effectively at the mercy of his directing abilities. He also opens his 1st act and closes his 2nd act with two of the best car chases in a movie since Ronin: no physics-defying CGI trickery here, just expert stunt driving and judicious camerawork/editing to remind you of how good craftsmanship can make action 'sing' in a movie.In short, this is Your Humble Reviewer's pick for movie of the year, of any kind. Some have shrugged it off for being a critic's darling or rejected it due to a bad ad campaign that made it look like another meatheaded action thriller... but they're wrong, dead wrong. It's a rare pleasure to see a filmmaker take familiar material and create some stunning through an inspired application of filmmaking skill. Drive is one of those occasions so you can believe the hype: this is going to be a major cult movie.

violence - the audience is effectively at the mercy of his directing abilities. He also opens his 1st act and closes his 2nd act with two of the best car chases in a movie since Ronin: no physics-defying CGI trickery here, just expert stunt driving and judicious camerawork/editing to remind you of how good craftsmanship can make action 'sing' in a movie.In short, this is Your Humble Reviewer's pick for movie of the year, of any kind. Some have shrugged it off for being a critic's darling or rejected it due to a bad ad campaign that made it look like another meatheaded action thriller... but they're wrong, dead wrong. It's a rare pleasure to see a filmmaker take familiar material and create some stunning through an inspired application of filmmaking skill. Drive is one of those occasions so you can believe the hype: this is going to be a major cult movie.