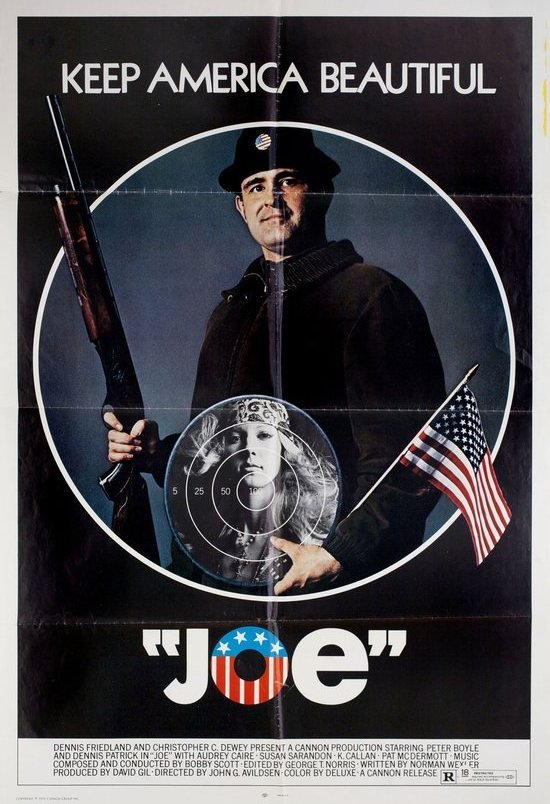

JOE (1970): The Silent Majority Goes Out For Blood

The 1970’s was a truly explosive era for filmmaking. The tumultuous nature of the times and new freedoms offered by the R-rating resulted in a number of film that pushed social and cultural boundaries in exciting ways. Even when they fall short of the mark, the most ambitious ones can still punch a viewer's buttons with ease. A fine example of the latter category is Joe, a rabble-rousing indie film produced by a pre-Golan & Globus Cannon that attracted both controversy and success.The film's episodic narrative starts off with Melissa (Susan Sarandon), a well-heeled suburbanite whose desire to escape her bourgeois upbringing has led her to live with drug dealer Frank (Patrick McDermott). When she has a pill-induced mental breakdown, he runs afoul of her ad exec father, Bill Compton (Dennis Patrick) - and he taunts him until Compton snaps and beats him to death. Compton stumbles into a bar and confesses his crime to a loud-mouth blue collar guy named Joe (Peter Boyle). Joe puts two and two together and tracks Compton down - only the twist is he doesn't want to blackmail Compton, he wants to befriend him since he sees the murder as a noble civic deed. The two become unlikely pals and Joe accompanies Compton to track his daughter down when she realizes her father's crime. They get in way over their heads, resulting in a tragic, bitterly ironic finale.Joe is undeniably a product of its times. It revels in the freedoms offered by the then-new rating system, dishing out a few startling outbursts of violence, a surprising amount of casual nudity and a barrage of profane dialogue from its title character. It also rejects the idea of clearcut heroes and villains to create a tale where no one is truly noble or evil: the civilized adults are portrayed as hypocritical in their morality and the young people are by turns foolishly naive about life and depressingly jaded towards ideas of right and wrong.This open-ended approach is both a strength and weakness - despite its honesty, the settles for a grim nihilism rather than taking a stand. As a result, the fascistic title character became an ironic hero to a number of conservatives fed up with their hippie offspring (there was an even an album entitled "Joe Speaks" that preserved the character's rants for posterity!)

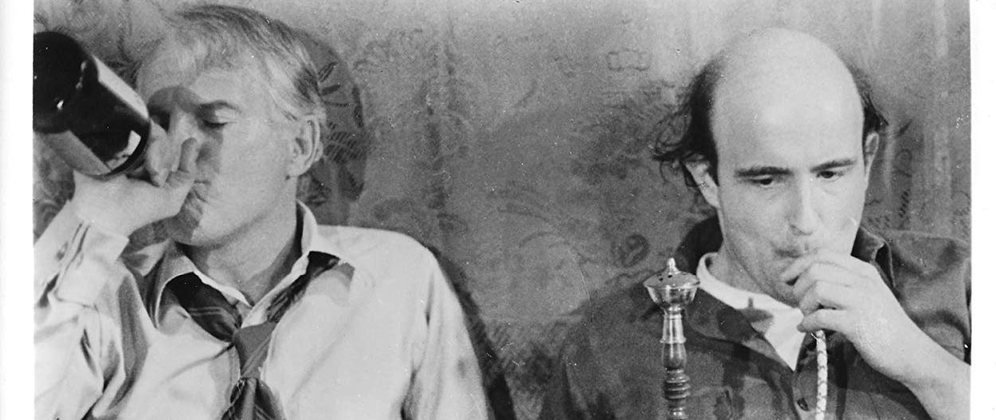

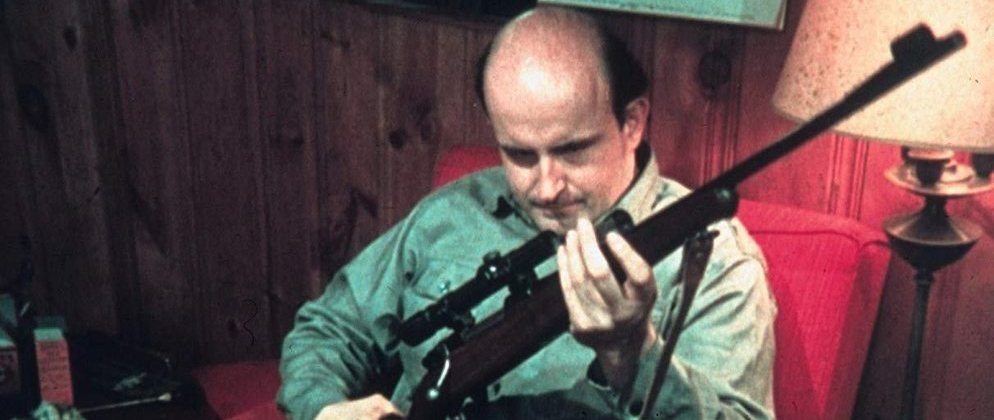

Compton stumbles into a bar and confesses his crime to a loud-mouth blue collar guy named Joe (Peter Boyle). Joe puts two and two together and tracks Compton down - only the twist is he doesn't want to blackmail Compton, he wants to befriend him since he sees the murder as a noble civic deed. The two become unlikely pals and Joe accompanies Compton to track his daughter down when she realizes her father's crime. They get in way over their heads, resulting in a tragic, bitterly ironic finale.Joe is undeniably a product of its times. It revels in the freedoms offered by the then-new rating system, dishing out a few startling outbursts of violence, a surprising amount of casual nudity and a barrage of profane dialogue from its title character. It also rejects the idea of clearcut heroes and villains to create a tale where no one is truly noble or evil: the civilized adults are portrayed as hypocritical in their morality and the young people are by turns foolishly naive about life and depressingly jaded towards ideas of right and wrong.This open-ended approach is both a strength and weakness - despite its honesty, the settles for a grim nihilism rather than taking a stand. As a result, the fascistic title character became an ironic hero to a number of conservatives fed up with their hippie offspring (there was an even an album entitled "Joe Speaks" that preserved the character's rants for posterity!) Still, Joe retains the power to provoke a strong response. Screenwriter Norman Wexler was in his forties when he wrote the script and it very much reflects a midlife crisis mentality - the two leads are both angered and frightened by the attitudes of the younger generation, yet they also feel a nagging sense of hollowness in their respectable lives. A few key scenes are rushed and the plotting relies on a few too many easy coincidences but the raw power of its content - and Wexler's ear for hilariously profane dialogue - ensure it remains compelling.A pre-Rocky John Avildsen directs the film with an experimental touch: some of his choices haven't dated well (some overtly literal use of pop music on the soundtrack, a few trippy visual and sonic affectations in the violent scenes) but his combination of atmospheric location shooting and ability to get unaffected performances from his cast keep the film from rolling off the rails.Best of all, Joe has an astonishing performance from Peter Boyle. Compton is the film's true main character - and '70s t.v. regular Dennis Patrick gives an underrated performance in this role - but it is Boyle who steals the show. He manages to take a character that most likely seemed repugnant on paper and makes him surprisingly likeable without defusing his hidden ugliness. One moment he's charming as he shows a childlike joy in his new friendship with Compton, the next minute he's terrifying as he beats some information out of a little hippie girl. His ability to capture this strange duality and make the character so charismatic is a testament to his skills, not to mention a good dry run for the characters he'd later play in Taxi Driver and Hardcore.

Still, Joe retains the power to provoke a strong response. Screenwriter Norman Wexler was in his forties when he wrote the script and it very much reflects a midlife crisis mentality - the two leads are both angered and frightened by the attitudes of the younger generation, yet they also feel a nagging sense of hollowness in their respectable lives. A few key scenes are rushed and the plotting relies on a few too many easy coincidences but the raw power of its content - and Wexler's ear for hilariously profane dialogue - ensure it remains compelling.A pre-Rocky John Avildsen directs the film with an experimental touch: some of his choices haven't dated well (some overtly literal use of pop music on the soundtrack, a few trippy visual and sonic affectations in the violent scenes) but his combination of atmospheric location shooting and ability to get unaffected performances from his cast keep the film from rolling off the rails.Best of all, Joe has an astonishing performance from Peter Boyle. Compton is the film's true main character - and '70s t.v. regular Dennis Patrick gives an underrated performance in this role - but it is Boyle who steals the show. He manages to take a character that most likely seemed repugnant on paper and makes him surprisingly likeable without defusing his hidden ugliness. One moment he's charming as he shows a childlike joy in his new friendship with Compton, the next minute he's terrifying as he beats some information out of a little hippie girl. His ability to capture this strange duality and make the character so charismatic is a testament to his skills, not to mention a good dry run for the characters he'd later play in Taxi Driver and Hardcore. Ultimately, the appeal of Joe will depend on your tolerance for its ambitious but ragged combination of experimentation and button-punching. Still, it's a must for anyone interested in the important American films of the 1970's. At the very least, it offers a memorable exercise in audience manipulation that still has the ability to provoke post-screening conversation.

Ultimately, the appeal of Joe will depend on your tolerance for its ambitious but ragged combination of experimentation and button-punching. Still, it's a must for anyone interested in the important American films of the 1970's. At the very least, it offers a memorable exercise in audience manipulation that still has the ability to provoke post-screening conversation.