The Best Cult Film Zine You Never Read: A Guide To The First Five Issues Of THE JOURNAL OF INTERSTITIAL CINEMA

The most interesting thing to happen in the cult movie scene in the last few years is the revival of the 'zine. Long after the internet supposedly murdered this personal form of expression, it seems the same computer tools have enabled an unexpected but welcome resurrection of this old-fashioned reading pleasure. Old warhorses like Cashiers Du Cinemart and Exploitation Retrospect have revived themselves to print new issues and more than a few freshly-minted 'zines have popped up, particularly now that desktop publishing and print-on-demand have made it easier to assemble and distribute them. In a world of fandom driven by blogs, a good 'zine has a few distinct advantages on its online competition. There's the tactile satisfaction of holding a carefully conceived publication, thumbing through the pages and toting it wherever you like. More importantly, the level of work involved in creating a publication encourages the better 'zine scribes to put more thought and craft into their work than you get from the average blog, which are often driven by the desire to be first instead of best.One of the most interesting 'zines to emerge in this revival era is The Journal Of Interstitial Cinema. It's five issues into its run yet it remains the best kept secret in the cult film 'zine world. This is partly because of the challenges involved in getting it: it operates under a cloud of underground-style secrecy, with information about it or its creators being hard to come by. Thankfully, all its issues are available on a print-on-demand basis via the Magcloud website so catching up on its run will be no problem for the devoted 'zine consumer.It's interesting to note that the Journal's two founders defy the current ethos of scribe-as-scene-celebrity by using pseudonyms to create an air of mystery: one uses the antiquarian-sounding nom de plume of R.J. Wheatpenny while the other goes by the more sci-fi moniker of Grog Ziklore. The difference in styles of name is reflected in their styles of writing: Wheatpenny favors lengthy, complex and scrupulously researched pieces that feel like something you might read in Film Comment while Ziklore goes for a classical 'zine style where a rowdy, Lester Bangs stream of consciousness approach dovetails with a deep, finely deta

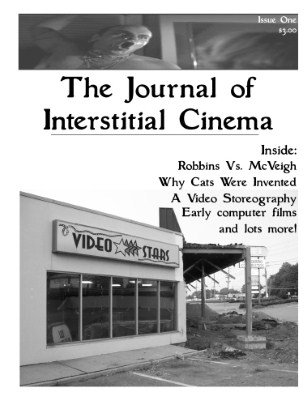

In a world of fandom driven by blogs, a good 'zine has a few distinct advantages on its online competition. There's the tactile satisfaction of holding a carefully conceived publication, thumbing through the pages and toting it wherever you like. More importantly, the level of work involved in creating a publication encourages the better 'zine scribes to put more thought and craft into their work than you get from the average blog, which are often driven by the desire to be first instead of best.One of the most interesting 'zines to emerge in this revival era is The Journal Of Interstitial Cinema. It's five issues into its run yet it remains the best kept secret in the cult film 'zine world. This is partly because of the challenges involved in getting it: it operates under a cloud of underground-style secrecy, with information about it or its creators being hard to come by. Thankfully, all its issues are available on a print-on-demand basis via the Magcloud website so catching up on its run will be no problem for the devoted 'zine consumer.It's interesting to note that the Journal's two founders defy the current ethos of scribe-as-scene-celebrity by using pseudonyms to create an air of mystery: one uses the antiquarian-sounding nom de plume of R.J. Wheatpenny while the other goes by the more sci-fi moniker of Grog Ziklore. The difference in styles of name is reflected in their styles of writing: Wheatpenny favors lengthy, complex and scrupulously researched pieces that feel like something you might read in Film Comment while Ziklore goes for a classical 'zine style where a rowdy, Lester Bangs stream of consciousness approach dovetails with a deep, finely deta iled sense of nostalgia.In the Journal's five issues, layout and graphics tend towards vintage 'zine simplicity but that ensures that the reader's focus remains on the content, which always has a few surprises up its sleeve. Issue Five also found them adding a new name to the roster in the Po Man. Like the other scribes involved in the Journal, he keeps his personal details private but this much can be said: he is a veteran of the 'zine scene who brings major interviewing and researching chops to the overall package. As his work in Issue Five reveals, he is also possessed of a sly wit.The following is a quick rundown of The Journal Of Interstitial Cinema's first five issues and what makes them worth the purchase. Schlockmania hopes you enjoy this informal overview... and tf the descriptions tantalize you (and they should if you're into cult cinema and 'zines) then you can get any of the following issues by clicking here: http://www.magcloud.com/browse/magazine/41635Issue #1: The first issue runs just 24 pages but there's a lot of rhetorical dexterity between its covers. Eclecticism is the name of the game here, with a review of the Taviani Brothers' historical film Luisa Sanfelice sitting next to a review of Computer Beach Party. The standout article is an extended piece on Arlington Road that compares and constrasts its relationship with real-life modern American history, specifically the case of Timothy McVeigh. It's smart, bitingly critic

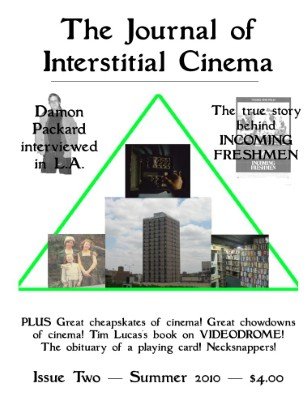

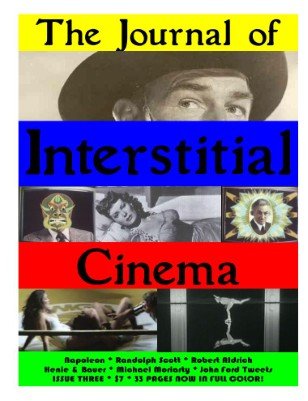

iled sense of nostalgia.In the Journal's five issues, layout and graphics tend towards vintage 'zine simplicity but that ensures that the reader's focus remains on the content, which always has a few surprises up its sleeve. Issue Five also found them adding a new name to the roster in the Po Man. Like the other scribes involved in the Journal, he keeps his personal details private but this much can be said: he is a veteran of the 'zine scene who brings major interviewing and researching chops to the overall package. As his work in Issue Five reveals, he is also possessed of a sly wit.The following is a quick rundown of The Journal Of Interstitial Cinema's first five issues and what makes them worth the purchase. Schlockmania hopes you enjoy this informal overview... and tf the descriptions tantalize you (and they should if you're into cult cinema and 'zines) then you can get any of the following issues by clicking here: http://www.magcloud.com/browse/magazine/41635Issue #1: The first issue runs just 24 pages but there's a lot of rhetorical dexterity between its covers. Eclecticism is the name of the game here, with a review of the Taviani Brothers' historical film Luisa Sanfelice sitting next to a review of Computer Beach Party. The standout article is an extended piece on Arlington Road that compares and constrasts its relationship with real-life modern American history, specifically the case of Timothy McVeigh. It's smart, bitingly critic al of Hollywood's desire to tackle political themes without going deep and more diligently researched and crafted than a lot of articles you'll read in mainstream film publications. Other highlights include an interview with the fictional character of Colt Hawker from Visiting Hours (an early example of Interstitial whimsy) and a "video storeography" that chronicles the video stores of the authors' youth. The latter piece will inspire both nostalgia and depression in reformed video store-holics of a certain age.Issue #2: You've probably never heard of Incoming Freshman but it gets a detailed exploration here, incorporating an interview with the director that reveals how his sincere indie film was reworked by other hands into crass sex comedy fodder. Also included is an interview with willfully iconoclastic underground filmmaker Damon Packard, Ziklore's uniquely personal review of the t.v. movie Death At Love House and a thoughtful overview of Tim Lucas' Videodrome book that gives Wheatpenny a chance to reflect on how it was a turning point in David Cronenberg's career. That said, the most creative piece might be a fictionalized article about a film student's suicide that becomes a ruthless satire of people's video-centric viewing habits.Issue #3: The rhetorical dexterity ascends to new heights here in a Wheatpenny piece that uses a critique of Machete and its kneejerk political content as the framework for an exploration of several Randolph Scott westerns and what they have to say about American society. Other highlights include an eye-opening look at the gonzo lunacy of Michael Moriarty's autobiography, Ziklore comparing the unexpected symmetry in Robert Aldrich's first and last films, Wheatpenny covering a few classic one-shot 'zines of the '70s and Ziklore giving a rundown of NYC video store haunts from his '90s era that have since passed into memory.

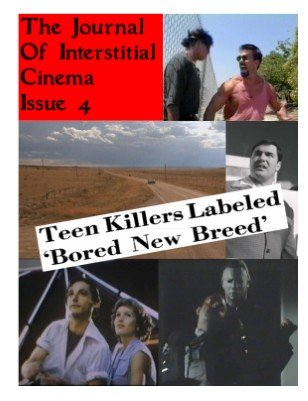

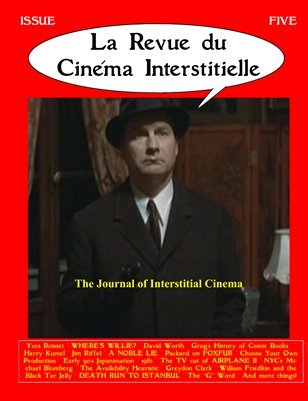

al of Hollywood's desire to tackle political themes without going deep and more diligently researched and crafted than a lot of articles you'll read in mainstream film publications. Other highlights include an interview with the fictional character of Colt Hawker from Visiting Hours (an early example of Interstitial whimsy) and a "video storeography" that chronicles the video stores of the authors' youth. The latter piece will inspire both nostalgia and depression in reformed video store-holics of a certain age.Issue #2: You've probably never heard of Incoming Freshman but it gets a detailed exploration here, incorporating an interview with the director that reveals how his sincere indie film was reworked by other hands into crass sex comedy fodder. Also included is an interview with willfully iconoclastic underground filmmaker Damon Packard, Ziklore's uniquely personal review of the t.v. movie Death At Love House and a thoughtful overview of Tim Lucas' Videodrome book that gives Wheatpenny a chance to reflect on how it was a turning point in David Cronenberg's career. That said, the most creative piece might be a fictionalized article about a film student's suicide that becomes a ruthless satire of people's video-centric viewing habits.Issue #3: The rhetorical dexterity ascends to new heights here in a Wheatpenny piece that uses a critique of Machete and its kneejerk political content as the framework for an exploration of several Randolph Scott westerns and what they have to say about American society. Other highlights include an eye-opening look at the gonzo lunacy of Michael Moriarty's autobiography, Ziklore comparing the unexpected symmetry in Robert Aldrich's first and last films, Wheatpenny covering a few classic one-shot 'zines of the '70s and Ziklore giving a rundown of NYC video store haunts from his '90s era that have since passed into memory. Issue #4: Cinematic anthropologists will get their money's worth here with a Wheatpenny article on lost films of the '90s that offers detailed historical and critical treatment of films like The Target Shoots First and The Woman Chaser. Ziklore offers a fun piece on why Halloween II (the original 1981 version) is his favorite film and a review of To All A Goodnight that allows him to tell a darkly humorous story about a convention encounter with David Hess. However, the most impressive writing here arrives in a piece called "If They Lived Ten More Years," in which Wheatpenny imagines what an extra decade would have done in the lives of Frank Borzage, Mario Bava, Andrei Tarkovsky and Don Simpson. It's the finest piece of whimsy in the Journal to date, mixing well-crafted fiction with pointed satire of how the film business warps the people working in it (the Simpson entry is particularly trenchant in this regard).Issue #5: this is the meatiest issue of the Journal to date, offering a whopping 68 pages of material. Thankfully, the authors maintain the consistency of the material here. Wheatpenny gives full sway to his love of pieces that are deep-dish in both research and intellectual content here: for instance, the nostalgically-remembered cinema year of 1982 is revealed to be a hotbed of changes in Hollywood film business, with corporate ownership and paradigm shifts in theatrical distribution laying the groundwork for the event movie-dominated approach that we live through today. He also explores the chaotic career of Harry Kumel via a review of a book on his career and offers a detailed film-by-film look at the career of French director Yves Boisset, whose career represents an interesting battle between the commercial and personalized political content.

Issue #4: Cinematic anthropologists will get their money's worth here with a Wheatpenny article on lost films of the '90s that offers detailed historical and critical treatment of films like The Target Shoots First and The Woman Chaser. Ziklore offers a fun piece on why Halloween II (the original 1981 version) is his favorite film and a review of To All A Goodnight that allows him to tell a darkly humorous story about a convention encounter with David Hess. However, the most impressive writing here arrives in a piece called "If They Lived Ten More Years," in which Wheatpenny imagines what an extra decade would have done in the lives of Frank Borzage, Mario Bava, Andrei Tarkovsky and Don Simpson. It's the finest piece of whimsy in the Journal to date, mixing well-crafted fiction with pointed satire of how the film business warps the people working in it (the Simpson entry is particularly trenchant in this regard).Issue #5: this is the meatiest issue of the Journal to date, offering a whopping 68 pages of material. Thankfully, the authors maintain the consistency of the material here. Wheatpenny gives full sway to his love of pieces that are deep-dish in both research and intellectual content here: for instance, the nostalgically-remembered cinema year of 1982 is revealed to be a hotbed of changes in Hollywood film business, with corporate ownership and paradigm shifts in theatrical distribution laying the groundwork for the event movie-dominated approach that we live through today. He also explores the chaotic career of Harry Kumel via a review of a book on his career and offers a detailed film-by-film look at the career of French director Yves Boisset, whose career represents an interesting battle between the commercial and personalized political content. Ziklore goes for shorter pieces, including a hilarious piece about a strange reference in Cruising that leads to a struggle to get an answer out of director William Friedkin and brief but pithy odes to '90s Japanese animation and comic books. He also serves up another extended chat with Damon Packard, in which he and Ziklore commiserate over their abhorrence of modern filmmaking trends while celebrating their love of vintage film and t.v. Po Man also adds some gems here, all oriented around the theme of MST3K and its negative influence on geek culture. He first illustrates the idea with an anecdote about how a convention screening of Empire Of The Ants went awry when one obnoxious fan decided he wants to be the entertainment instead of allowing the film's rough edges to speak for themselves. He also contributes interviews with David Worth and Greydon Clark, filmmakers who have gotten the MST3K treatment, to get their thoughts on the show and its influence.A final note: please understand that these capsule overviews can't cover all the interesting and engagingly offbeat fare in this 'zine. The Journal scribes do more with a regular magazine length than some of their competitors do with 200 pages and there's no way to cover it all without going on forever. Schlockmania encourages you to pick up some issues for yourself and explore their loving treatment of the arcane.

Ziklore goes for shorter pieces, including a hilarious piece about a strange reference in Cruising that leads to a struggle to get an answer out of director William Friedkin and brief but pithy odes to '90s Japanese animation and comic books. He also serves up another extended chat with Damon Packard, in which he and Ziklore commiserate over their abhorrence of modern filmmaking trends while celebrating their love of vintage film and t.v. Po Man also adds some gems here, all oriented around the theme of MST3K and its negative influence on geek culture. He first illustrates the idea with an anecdote about how a convention screening of Empire Of The Ants went awry when one obnoxious fan decided he wants to be the entertainment instead of allowing the film's rough edges to speak for themselves. He also contributes interviews with David Worth and Greydon Clark, filmmakers who have gotten the MST3K treatment, to get their thoughts on the show and its influence.A final note: please understand that these capsule overviews can't cover all the interesting and engagingly offbeat fare in this 'zine. The Journal scribes do more with a regular magazine length than some of their competitors do with 200 pages and there's no way to cover it all without going on forever. Schlockmania encourages you to pick up some issues for yourself and explore their loving treatment of the arcane.