STRAW DOGS (1971 Version): No Answers, Only Questions And Bloodshed

Sam Peckinpah was one of cinema's great provocateurs. He had greater range than he is usually given credit for (see The Ballad Of Cable Hogue or Junior Bonner for a look at his gentler, more reflective side) but he found his greatest success in being confrontational. He specialty was digging into the darkest, most difficult elements of the human condition - violence, machismo, territorial impulses, the thin line between civility and savagery - and doing so in a way that drags the audience right into the thick of the philosophical/visceral conflict. Straw Dogs is the ultimate example of Peckinpah's aesthetic rabble rousing. The Wild Bunch might have been the film that earned him the crown as godfather of the cinematic blood ballet but Straw Dogs is the film that brought the bloodshed right to the audience's doorstep and challenged their notions of how one should respond to the threat of violence (and its onscreen depiction). Forty years after its initial release, it can still get right under a viewer's skin.(*spoilers ahead...*)The

Straw Dogs is the ultimate example of Peckinpah's aesthetic rabble rousing. The Wild Bunch might have been the film that earned him the crown as godfather of the cinematic blood ballet but Straw Dogs is the film that brought the bloodshed right to the audience's doorstep and challenged their notions of how one should respond to the threat of violence (and its onscreen depiction). Forty years after its initial release, it can still get right under a viewer's skin.(*spoilers ahead...*)The  (anti-)hero of Straw Dogs is David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman), a mathematician who has retreated from the chaos of 1971-era America to a quiet English village that happens to be the hometown of his wife, Amy (Susan George). David tries to ingratiate himself with the locals - including Charlie (Del Henney), Amy's former lover - by hiring them to remodel the college they are living in. These men are a resentful group and, sensing easy prey, begin to passive-aggressively goad David. Fearing confrontation, David backs away - earning him the contempt of both the men and Amy.

(anti-)hero of Straw Dogs is David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman), a mathematician who has retreated from the chaos of 1971-era America to a quiet English village that happens to be the hometown of his wife, Amy (Susan George). David tries to ingratiate himself with the locals - including Charlie (Del Henney), Amy's former lover - by hiring them to remodel the college they are living in. These men are a resentful group and, sensing easy prey, begin to passive-aggressively goad David. Fearing confrontation, David backs away - earning him the contempt of both the men and Amy. When David goes on a hunting trip with the men in an attempt to prove himself as one of the guys, Charlie takes advantage of the situation to confront Amy alone. The situation devolves into a rape and further spirals out of control when another man gets involved. Amy remains silent about the incident when David returns home, resigned to the idea that he's incapable of defending her. However, David will show what he is capable of when fate places him in the middle of a tragic incident involving Henry Niles (David Warner), a man-child hated by the locals. He fights back when his home is attacked - and the results are dire for everyone involved.

When David goes on a hunting trip with the men in an attempt to prove himself as one of the guys, Charlie takes advantage of the situation to confront Amy alone. The situation devolves into a rape and further spirals out of control when another man gets involved. Amy remains silent about the incident when David returns home, resigned to the idea that he's incapable of defending her. However, David will show what he is capable of when fate places him in the middle of a tragic incident involving Henry Niles (David Warner), a man-child hated by the locals. He fights back when his home is attacked - and the results are dire for everyone involved. In many critical circles, Straw Dogs is viewed as a simple-minded cinematic provocation that exists to punch the viewer buttons - in fact, a lot of review of the 2011 remake of this film often downplayed their criticism of the remake with a "well, the first one was no work of art" line of reasoning. Those perceptive enough to look for a theme often dismiss it as a fascistic glorification of violence. That said, these responses oversimplify what it is going on here. As with so many of Peckinpah's films, it is much more complex than many people notice because its surface effects are so powerful.

In many critical circles, Straw Dogs is viewed as a simple-minded cinematic provocation that exists to punch the viewer buttons - in fact, a lot of review of the 2011 remake of this film often downplayed their criticism of the remake with a "well, the first one was no work of art" line of reasoning. Those perceptive enough to look for a theme often dismiss it as a fascistic glorification of violence. That said, these responses oversimplify what it is going on here. As with so many of Peckinpah's films, it is much more complex than many people notice because its surface effects are so powerful. If you can look past the violence and tension, you will realize that Straw Dogs isn't telling the viewer what to think. Peckinpah is more interested in forcing the viewer to confront their attitudes towards violence and pacifism by presenting them with a boiling pot-style hypothetical situation. David and Amy are the protagonists, but only by default: neither is entirely sympathetic and both have a tendency to escalate dangerous situations through their personality flaws. The viewer is given no clear identification figure to cue us on how to react to the story's events, thus forcing the viewer to make their own decisions on who is right and who is wrong.

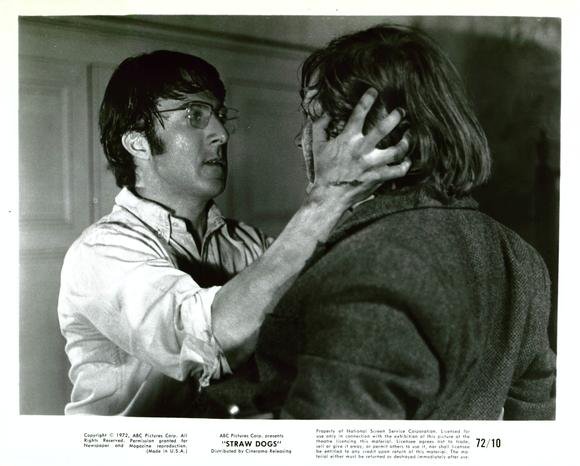

If you can look past the violence and tension, you will realize that Straw Dogs isn't telling the viewer what to think. Peckinpah is more interested in forcing the viewer to confront their attitudes towards violence and pacifism by presenting them with a boiling pot-style hypothetical situation. David and Amy are the protagonists, but only by default: neither is entirely sympathetic and both have a tendency to escalate dangerous situations through their personality flaws. The viewer is given no clear identification figure to cue us on how to react to the story's events, thus forcing the viewer to make their own decisions on who is right and who is wrong. However, that doesn't mean the film's auteur doesn't make his voice felt in Straw Dogs. Peckinpah has a contemptuous attitude towards pacifism, at least in the form espoused by David. He famously told his critics that David is not a hero: instead the director saw him as the villain because his refusal to confront tense situations brings things to a boiling point, causing tragedies that might have been avoided earlier. That said, the oft-made assertion that Peckinpah presents violence as an answer really isn't true either: David becomes frightening instead of manly when he fights back and the finale suggests that he has lost both Amy and his sanity.

However, that doesn't mean the film's auteur doesn't make his voice felt in Straw Dogs. Peckinpah has a contemptuous attitude towards pacifism, at least in the form espoused by David. He famously told his critics that David is not a hero: instead the director saw him as the villain because his refusal to confront tense situations brings things to a boiling point, causing tragedies that might have been avoided earlier. That said, the oft-made assertion that Peckinpah presents violence as an answer really isn't true either: David becomes frightening instead of manly when he fights back and the finale suggests that he has lost both Amy and his sanity. Even the film's highly controversial rape scene isn't as clear-cut as it is often portrayed. though the act is appropriately presented as a horrifying violation, the scene is also infused with the unfinished emotional business lingering between these former lovers. To dismiss it as "she was asking for it" scene (the usual critical hatchet-job on this scene) is to misread the complexity of the betrayal that Amy suffers here, not to mention the complexity of how the director deals with it. Peckinpah's real thoughts on her ordeal are shown clearly in a subsequent scene: in an unforgettable, brilliantly edited sequence, Amy sees her attackers at a social gathering and is

Even the film's highly controversial rape scene isn't as clear-cut as it is often portrayed. though the act is appropriately presented as a horrifying violation, the scene is also infused with the unfinished emotional business lingering between these former lovers. To dismiss it as "she was asking for it" scene (the usual critical hatchet-job on this scene) is to misread the complexity of the betrayal that Amy suffers here, not to mention the complexity of how the director deals with it. Peckinpah's real thoughts on her ordeal are shown clearly in a subsequent scene: in an unforgettable, brilliantly edited sequence, Amy sees her attackers at a social gathering and is  unnerved by jagged flashbacks of the rape. Peckinpah's handling of this scene reinforces the horror of the attack: even if he is critical of the character, he is sympathetic to her suffering and makes the audience feel it by showing her pain.It's also worth noting how fantastic the acting is across the board here: this is an aspect of Straw Dogs that is usually glossed over in the rush to condemn it. Hoffman overcomes the ultimately unsympathetic nature of David by layering on the jittery, method-actor charm that defined his best work during the 1970's. George gives a wildly underrated performance: she generates an

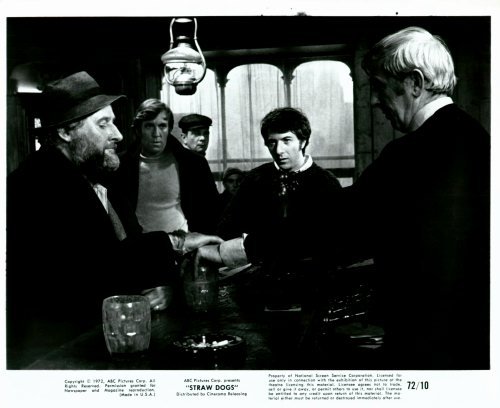

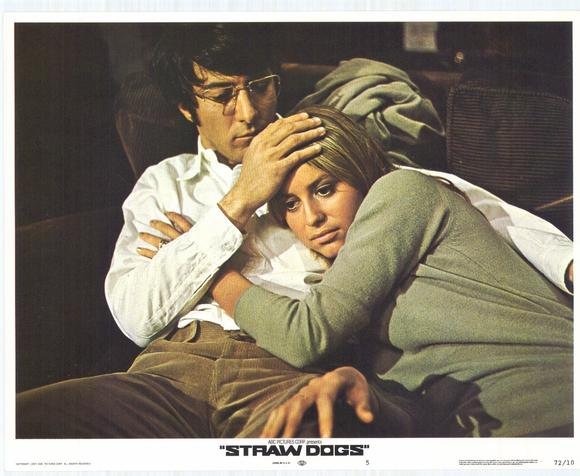

unnerved by jagged flashbacks of the rape. Peckinpah's handling of this scene reinforces the horror of the attack: even if he is critical of the character, he is sympathetic to her suffering and makes the audience feel it by showing her pain.It's also worth noting how fantastic the acting is across the board here: this is an aspect of Straw Dogs that is usually glossed over in the rush to condemn it. Hoffman overcomes the ultimately unsympathetic nature of David by layering on the jittery, method-actor charm that defined his best work during the 1970's. George gives a wildly underrated performance: she generates an  impressive chemistry with Hoffman and their scenes together show a tremendous amount of subtle, non-verbal acting skill. The villagers are all effortlessly convincing, particularly Henney as the alpha-male reverse image of David. Particularly worthy or praise are unforgettable character turns by Warner as the sometimes charming, sometimes scary Henry and Peter Vaughan, who is terrifying as the patriarch who encourages the thugs in their behavior (one of many "bad dad" figures in Peckinpah's films).

impressive chemistry with Hoffman and their scenes together show a tremendous amount of subtle, non-verbal acting skill. The villagers are all effortlessly convincing, particularly Henney as the alpha-male reverse image of David. Particularly worthy or praise are unforgettable character turns by Warner as the sometimes charming, sometimes scary Henry and Peter Vaughan, who is terrifying as the patriarch who encourages the thugs in their behavior (one of many "bad dad" figures in Peckinpah's films). Finally, Peckinpah deserves praise for the tremendous skill he invested in bringing this film to life. He gets a sharp, consistent level of performances from his cast to set the mood: as mentioned before, the subtlety of the domestic scenes between David and Amy is grossly underrated. The script, which he adapted from a novel with David Zelag Goodman, is admirable in its willingness to be ambivalent toward its characters and ambiguous in its presentation of emotionally charged events. He also got the best out of his behind-the-scenes collaborators: John Coquillon's cinematography has an earthy yet artful feel, perfectly matched to

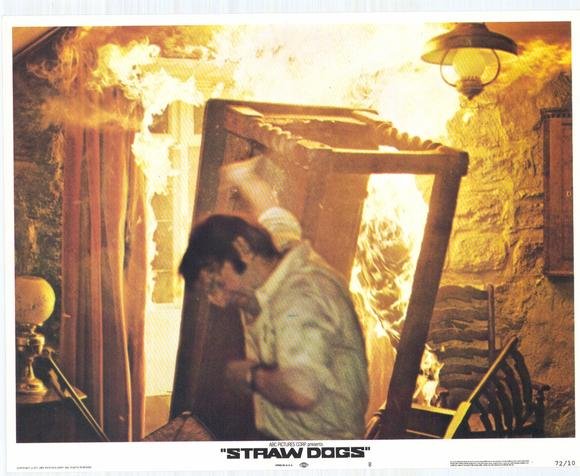

Finally, Peckinpah deserves praise for the tremendous skill he invested in bringing this film to life. He gets a sharp, consistent level of performances from his cast to set the mood: as mentioned before, the subtlety of the domestic scenes between David and Amy is grossly underrated. The script, which he adapted from a novel with David Zelag Goodman, is admirable in its willingness to be ambivalent toward its characters and ambiguous in its presentation of emotionally charged events. He also got the best out of his behind-the-scenes collaborators: John Coquillon's cinematography has an earthy yet artful feel, perfectly matched to  both the setting and the story's mood, and the montage technique of editors Paul Davies, Tony Lawson and Roger Spottiswoode plays a crucial role in giving the film its shape and kinetic drive.That said, the best example of his skills come in the finale. The siege on David and Amy's home is a master class in how to stage action and suspense to achieve a tremendous visceral effect. The jagged editing and artful deployment of slow motion in this extended sequence have been copied for years - but the artful direction of actors and the complexity of how it forces the audience to shift its attitudes toward the characters during its twists and turns have never been duplicated. It's a highly sophisticate

both the setting and the story's mood, and the montage technique of editors Paul Davies, Tony Lawson and Roger Spottiswoode plays a crucial role in giving the film its shape and kinetic drive.That said, the best example of his skills come in the finale. The siege on David and Amy's home is a master class in how to stage action and suspense to achieve a tremendous visceral effect. The jagged editing and artful deployment of slow motion in this extended sequence have been copied for years - but the artful direction of actors and the complexity of how it forces the audience to shift its attitudes toward the characters during its twists and turns have never been duplicated. It's a highly sophisticate d piece of work that lands its punches no matter how many times you watch it.Simply put, the original version of Straw Dogs is smarter, more complex and far more ambiguous than it is perceived to be. In both emotional and psychological terms, it puts you right in the heart of the conflict and demands that you make up your mind for yourself. Few directors are ever willing to take such a risky chance - and that kind of artistic bravery is why Sam Peckinpah was, is and always will be one of cinema's finest directors.

d piece of work that lands its punches no matter how many times you watch it.Simply put, the original version of Straw Dogs is smarter, more complex and far more ambiguous than it is perceived to be. In both emotional and psychological terms, it puts you right in the heart of the conflict and demands that you make up your mind for yourself. Few directors are ever willing to take such a risky chance - and that kind of artistic bravery is why Sam Peckinpah was, is and always will be one of cinema's finest directors.